By Zihao Wong and Diancong Liu

A creative response to Ming Wong’s Wayang Spaceship, and in collaboration with Singapore Art Museum’s The Everyday Museum.

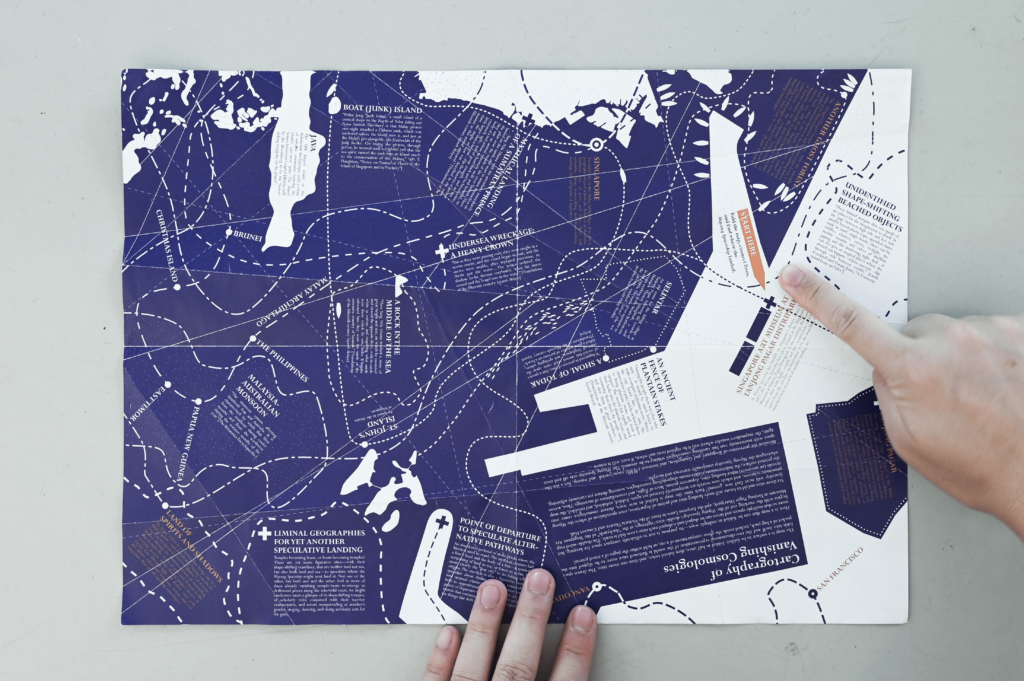

“How will we draw a map for the Wayang Spaceship? Where did it come from? How did it land? Where is it going from here?

And as the Wayang Spaceship lifts off—once again, like the numerous times the travelling theatre has been assembled, disassembled, and reassembled—two (self-proclaimed) design-cartographers Liu Diancong and Wong Zihao haphazardly recollect the multiple spaces and times that the Wayang Spaceship has sailed through and docked at.

(Not) By chance, the latter hails from the island-city of Singapore, while the former calls the port-city of Guangzhou home. Between them and between yueju/jyutkek and wayang, they begin the onerous task of tracing the spaceship’s trajectory as it moved and shape-shifted across distant worlds. Too numerous, and much too fleeting and fragile, their map can only hint at the Wayang Spaceship’s multiple landing points—these are after all quickly vanishing cosmologies.

Unlike traditional maps that are drawn to pinpoint places with measured precision and accuracy, this map speaks of unfixing things in space, expanding into an imagination of fluid and mobile cosmologies—appearing and disappearing, shaping and shifting, colliding and coming apart.”

How to read Cartography of Vanishing Cosmologies

1.Locate the starting position on the map, indicated by the building footprint1 of the Singapore Art Museum at Tanjong Pagar Distripark. This is one of the last places the Wayang Spaceship was seen.

“A Wayang Spaceship has landed on Singapore’s shores. Since July 2022, the Wayang Spaceship has taken ground at the Singapore Art Museum at Tanjong Pagar Distripark. In the evenings, the spaceship comes alive with light, sound, and film reminiscent of Chinese opera from the old days. In December 2023, the travelling theatre launched away in search of another landing site.”

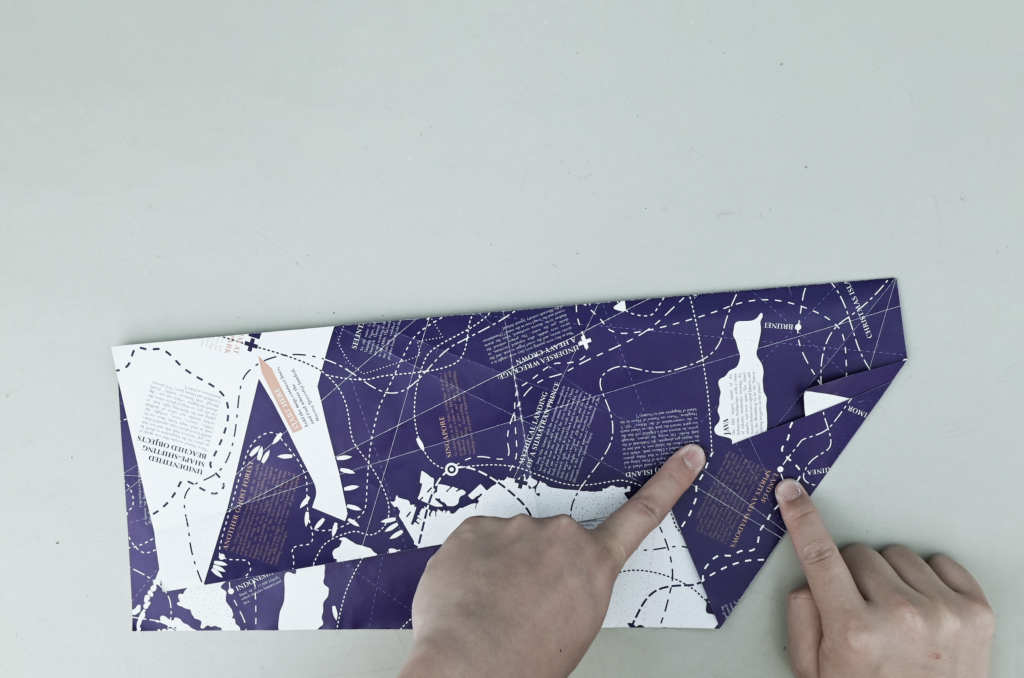

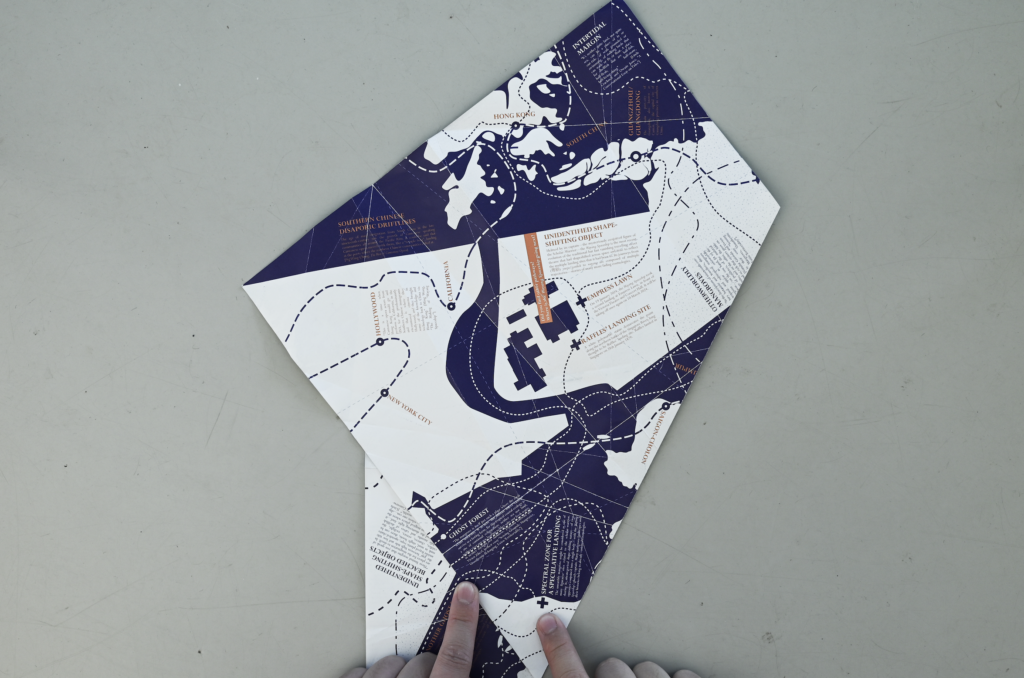

2. As you follow the dotted line leading away from the starting point, make a diagonal fold across the map, so that the dotted line on the opposite surface aligns with the path that you took. With your finger, trace the line as it moves along the opposite surface, and another cosmological network comes into view.

“Indian Sailing Boats. Indian sailing vessels connected the distanced ports of South and Southeast Asia, offering their sailing canvases as humble weatherproofing tarpaulin shelters in places outside of India. Boat technologies were monsoonal technologies, connecting across the tropics.”

Following the line further, a next entry might read:

“Temple-Boat. In the 1960s-70s, Indian sailing canvases were used to construct the tents of travelling wayang theatres, keeping the stages that entertained the gods in the seventh lunar month dry but also cool from the wet and hot tropical weather.”

3. Fold the map in more ways, align your trajectory onto new dotted pathways, and discover more accidental cosmologies formed in the process of folding and unfolding the map. See if you can wound up at the Empress Lawn, where the Wayang Spaceship moved to from the Singapore Art Museum at Tanjong Pagar Distripark. Take these instructions as mere recommendations on how to use the map. You should allow yourself the opportunity to select a different point to start, fold the map differently, follow different lines, and stumble into other cosmologies.

Fold and Unfold

The Merriam-Webster dictionary defines “folding” as the act of “laying one part over another part” of something, as in folding a letter, a drawing, or a map. To “fold” is also to “clasp” or to “incorporate closely”, as one would fold their hands together, or when events are enfolded one with another. To “fold” is then to layer, as seen in pleating a sheet of paper, where the paper becomes “doubled over”; the outcome extends to meanings of “multiplying” when the word is used as a suffix: two-fold, three-fold, and a hundred-fold.

But a “fold” also brings the notion of concealment, as things go from being seen on the surface to a state of not being seen when surfaces become layered one atop another. Conversely, when unfolding a map, the folds open and the map’s hidden contents come into full visibility once again. To “unfold” is hence to “reveal”—that is, to “open to view”, and to “become known”.

A different way to read Cartography of Vanishing Cosmologies

4. We might start instead from another place. This time, we begin from the corner of one side of the map, tracing a path from the landform labelled “Guangzhou/Guangdong”.

“The main port-city of Guangzhou, also known as Canton, is the capital city of Guangdong province in southern China.”

5. While following the coastline, fold the map to reconfigure the shape of the landform, merging one coastline with another. From one port-city, we could end up on another island.

“Java. The fifth largest island of the Indonesian Archipelago, with a chain of volcanic mountains forming the island’s east-west spine. The island houses Indonesia’s capital Jakarta, said by Bloomberg to be the ‘fastest-sinking megacity on the planet’.”

6. From Java, we might decide to now hop off the island and follow a boat as it journeys across the ocean. Another fold of the map connects the dotted lines to an ethereal place in the middle of the sea.

“Land of spirits and shadows. ‘Ma Hyang’ refers to a journey that brings one to a land of spirits—and its derivative ‘wayang’ can also be traced to the Javanese word for ‘shadow’, as it is also known through the ancient art form of storytelling that brought the realm of the gods and demons to the everyday person, in the shadow puppet theatre of ‘wayang kulit’. Through light and shadow came gods and spirits, rulers and kingdoms, heroes and evil magicians. These are all vanishing cosmologies.”

Unfolding a Travelling Stage

19 January, 7.30pm. The opening night of 2024’s Light to Night Festival was a very wet one indeed. Carrying umbrellas amidst a tropical downpour, we braved the weather and trudged to the corner of the soggy Empress Lawn in front of the Victoria Theatre and Concert Hall, where Ming Wong’s Wayang Spaceship perched lightly on the ground—spotted again since it last set off from the Tanjong Pagar Distripark. It is a makeshift structure of timber stakes lashed together with ropes, supporting an elevated stage. A tent made of silvery weatherproof canvas sheltered the stage and its electrically lit interiors from the ongoing rain. Our reflections appeared warped when we peered into the acrylic panels lighted by fluorescent tubes with dichroic film installed on the wayang stage.

Serendipitously, we mused at how the wooden stage in front of us paradoxically made tangible both the distance and nearness of our home cities—between Guangzhou and Singapore. Its temporary location next to the statue of Stamford Raffles overlooking the Singapore River reminded us of the multiple landing points that brought ideas, things, people, cultures—and indeed whole cosmologies—from faraway places to sediment and take root in new ones.

Like other wayang stages from the past, we imagined how this stage, and its Cantonese opera traditions, had travelled across the South China Sea beginning from its home grounds in Guangzhou. Over time, the resultant stage can be thought of as an assemblage of many places: each place from before leaving its traces in the next; each fragment of a Cantonese opera stage morphing with other fragments across space and time, to become (re)assembled in new ways. What is the name familiar to most Singaporeans when referring to Cantonese opera? “Wayang”. The thought left us pondering the “Javanese-ness” of an originally Cantonese art form.

Back in the studio, we folded a little paper model of the Wayang Spaceship. It had mirror-like surfaces, and we imagined how the spaceship reflected its surroundings wherever it landed, shape-shifting as it blended into places, but also reconfiguring itself in new ways each time it left for another place. The silvery folded surfaces of our paper spaceship reflected but also made distorted images wherever it was placed.

The Wayang Spaceship at the Empress Lawn, in front of Victoria Theatre and Concert Hall.

More ways to read Cartography of Vanishing Cosmologies

7. Back on Java, we might trace a different coastline across a fold of the map, to the opposite side, arriving at some “Otherworldly Mangroves”. Continuing with an additional fold, the dotted line brings us to a cluster of boats mooring along yet another coastline.

“Another ghost forest. The Chengal tree is a tropical hardwood known to be used for building houses and boats, owing to the wood’s resistance to tropical wetness, rot, and decay. Thought to be extinct in Singapore, these forms of marine timber are like their constructed house-boat counterparts—or the temporary ‘temple-boats’ of travelling wayang stages—all part of multiple vanishing cosmologies.”

8. Unfolding and refolding the page to locate a different boat journey to set off with, more vanishing cosmologies come into view.

“Spectral zone for a speculative landing. The unearthly mangrove might be considered as one of many figurative sites related to the scholar-warrior, sharing its uncategorical shape-shifting nature—of two opposites conjoined into a single body—with the Wayang Spaceship’s ghostly captain. Many mangrove landscapes and their histories belong to already vanished cosmologies.”

Unfolded Topo/graphy

In conceptualising the Wayang Spaceship, Ming Wong imagines “a temple boat cast adrift on land, visible only once the floodwaters recede… It’s almost invisible because of its camouflage, strategically angled in a mirrored garden. If you were not looking for it, you would not find it.” Neither house nor boat, but both, the Wayang Spaceship draws close resemblances to the shape-shifting landscapes of the intertidal margins of coastlines—neither water nor land, but both.

The intertidal zone is the shape-shifting part of coastal geographies that drains away to reveal land in the low-tide, and reverts into the sea in high-tide. The artist Linda Cracknell and cultural geographer Owain Jones, in A Conversational Essay on Tides describe these places as “liminal margins”, giving rise to playful imagination from the unusual conjoining of opposing entities found within intertidal zones: “of seals grounded or swimming, of stalking birds that can wade or fly or float [and] a place for shellfish that are half-fish, half-flesh; half-stone, half-living-thing.” Intertidal margins, including mangrove forests and coastal reefs, are extraordinary places, but like the Wayang Spaceship and its multiple landing points, they belong to quickly fading cosmologies. The temporal natures of shape-shifting intertidal coasts—appearing and disappearing with the ebb and flow of the sea—make it particularly difficult to visualise on cartographic maps that cannot help but fix the coast in place by drawing a line.

In our work as design-researchers, we take particular interest in the potential of art and design to promote alternative ways of seeing (from within), engaging with, and caring for, landscapes in crisis. The notion of “topography”—drawing from the term’s archaic meanings in Greek: “topos: place”, and “graphia: a form of writing/drawing”– appeals to our work. It mimics a wandering method of story-telling places into being. In the process of inventing Cartography of Vanishing Cosmologies, we asked how could we expand on our intertidal thinking—and ways of seeing—to draw a map of shape-shifting “topographies”? Can a map shape-shift, and with each new reconfiguration, formulate new worlds in our imagination? What is a map for wandering, rather than exacting locations? How can a map tell of places connected across distant and vanishing cosmologies?

Intertidal reefs at Pulau Hantu.

The Wayang Spaceship on its closing performance, 10 March 2024.

A last note on reading Cartography of Vanishing Cosmologies

9. Congratulations if you found your way to Empress Lawn. Or did you end up in one of the Wayang Spaceship’s other landing sites?

“Liminal geographies for yet another speculative landing. Temples becoming boats, or boats becoming temples? These are yet more figurative sites to speculate where the Wayang Spaceship might land at next. And as more of these already vanishing temple-boats re-emerge as driftwood pieces along the intertidal coast, we might catch once more a glimpse of its shape-shifting troupes, of scholarly roles conjoined with their warrior counterparts, and actors masquerading as another’s gender, singing, dancing, and doing acrobatic acts for the gods.”

Folding and Unfolding a Shape-shifting Map

“The map is a surface to be folded: folded in half once, then halved twice, and then one more time. The drawn space folds into itself and the two-dimensional representation of the world is flattened once more to be slipped into the pocket of a bag pack, tucked inside the glove compartment of a car, or held within the pages of a travel journal.

Here is a map that can be folded in multiple ways—its purpose is not to efficiently compact space for keeping, but more so that multiple spaces and times can be shaped and reshaped each time a new fold is made. Each time the map is folded in new ways, distant cosmologies come into proximate relations, and whole new worlds are temporarily formed yet again. Folded, unfolded, and refolded, the map reveals (or uncovers) other landing sites, departure points, lines of flight, and constellations of meanings. Thus, across the printed surface, the indeterminate routes create shape-shifting cosmologies, seeming distant yet curiously adjoining, whereupon the Wayang Spaceship continually traverses and morphs.

Between the port-cities of Singapore and Guangzhou, and between yueju/jyutkek and wayang, lies a sea-like space with numerously vast but vanishing cosmologies waiting to be crossed. The Wayang Spaceship sets off and—once again, the mapmakers wonder where it will be sighted next and when, if ever, will it return…”

*All photographs are by the authors.

1 – The border of a building drawn along the exterior walls, to create a polygon, representing the total area of the building.